It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

– Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations

Adam Smith explains the classic “order in chaos” concept in his masterpiece. But in a connected world, modern organizations need a little more stewardship to survive.

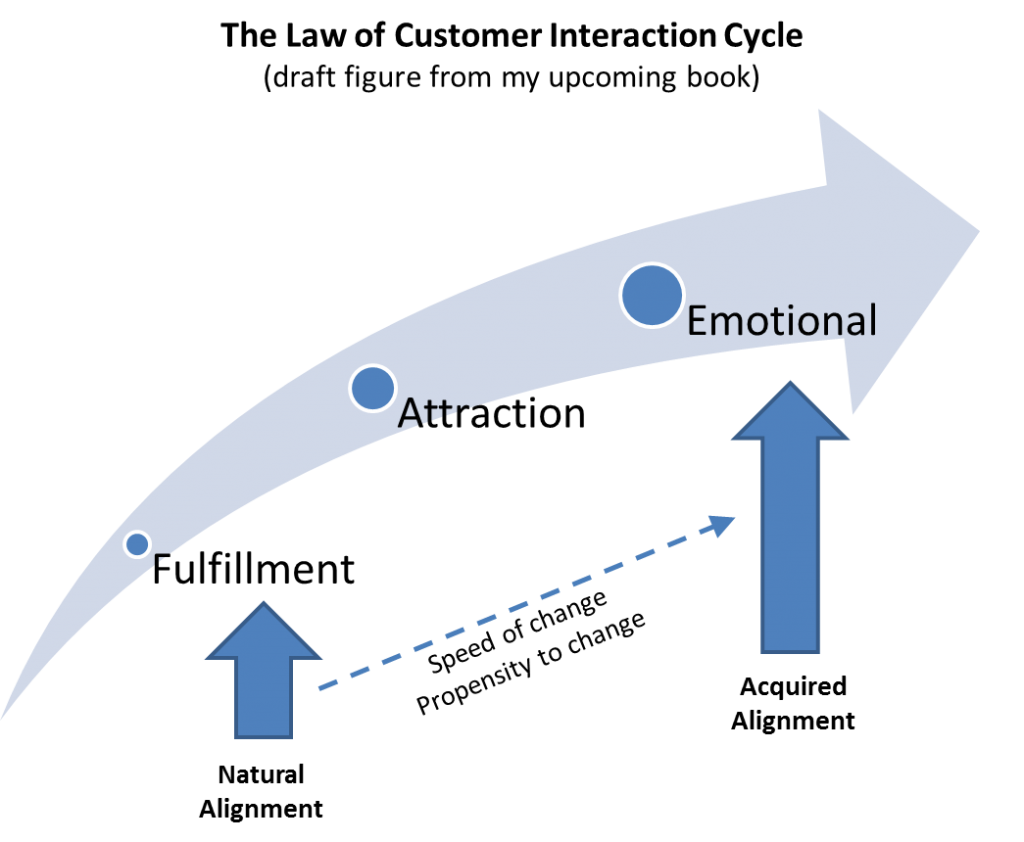

How do your customers interact with you? The Law of Presenting is about presenting a company aligned to its mission statement and raison d’etre, not as individual business units or products. The difference is stark. A mission statement is often broad and all encompassing, arising from recognition of a customer need that must be addressed. At founding, or even when a new business line is launched, the goals are lofty, focused on the customer, powered by grit and determination of the founders as they see the potential in meeting the need, and fueled by the passionate energy that accompanies the thrill of being at the helm of driving this agenda. But after all the organizational dynamics and business constraints have taken their toll, what results is a fragmented firm chasing to meet fragmented financial targets. The result is often obsolescence or the position of an also ran struggling for market share in a crowded market. It takes strong leadership and a very focused, market aligned product set for a firm to stay relevant to its customers.

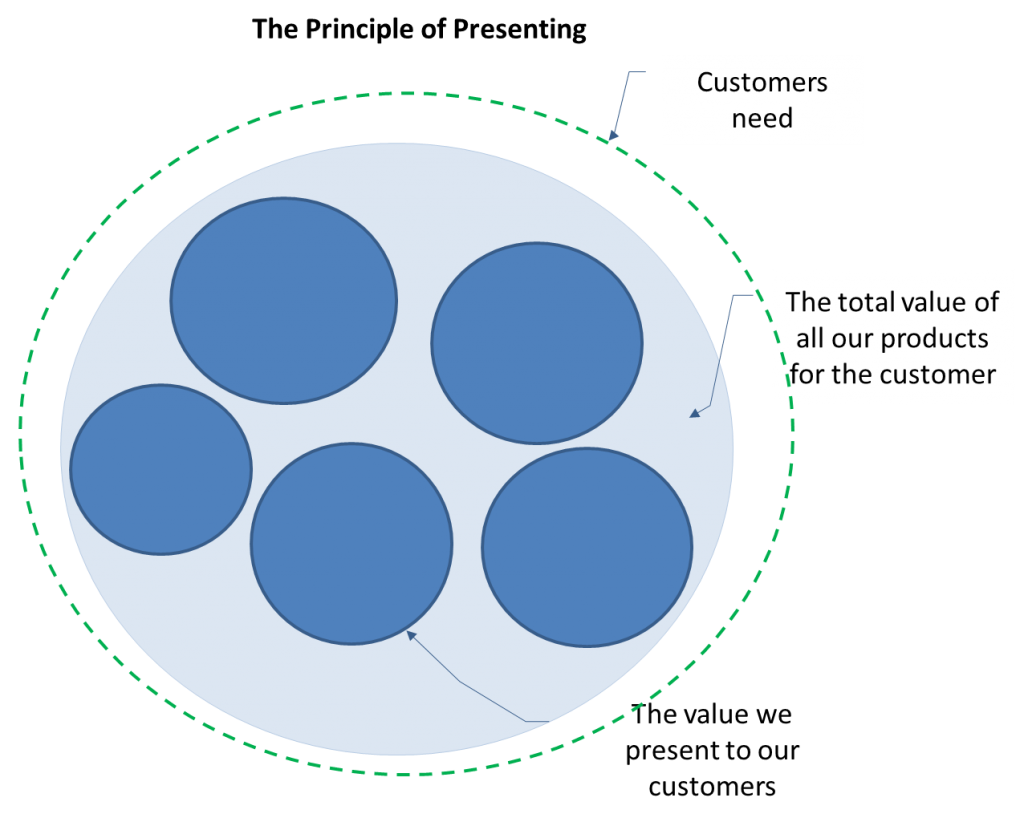

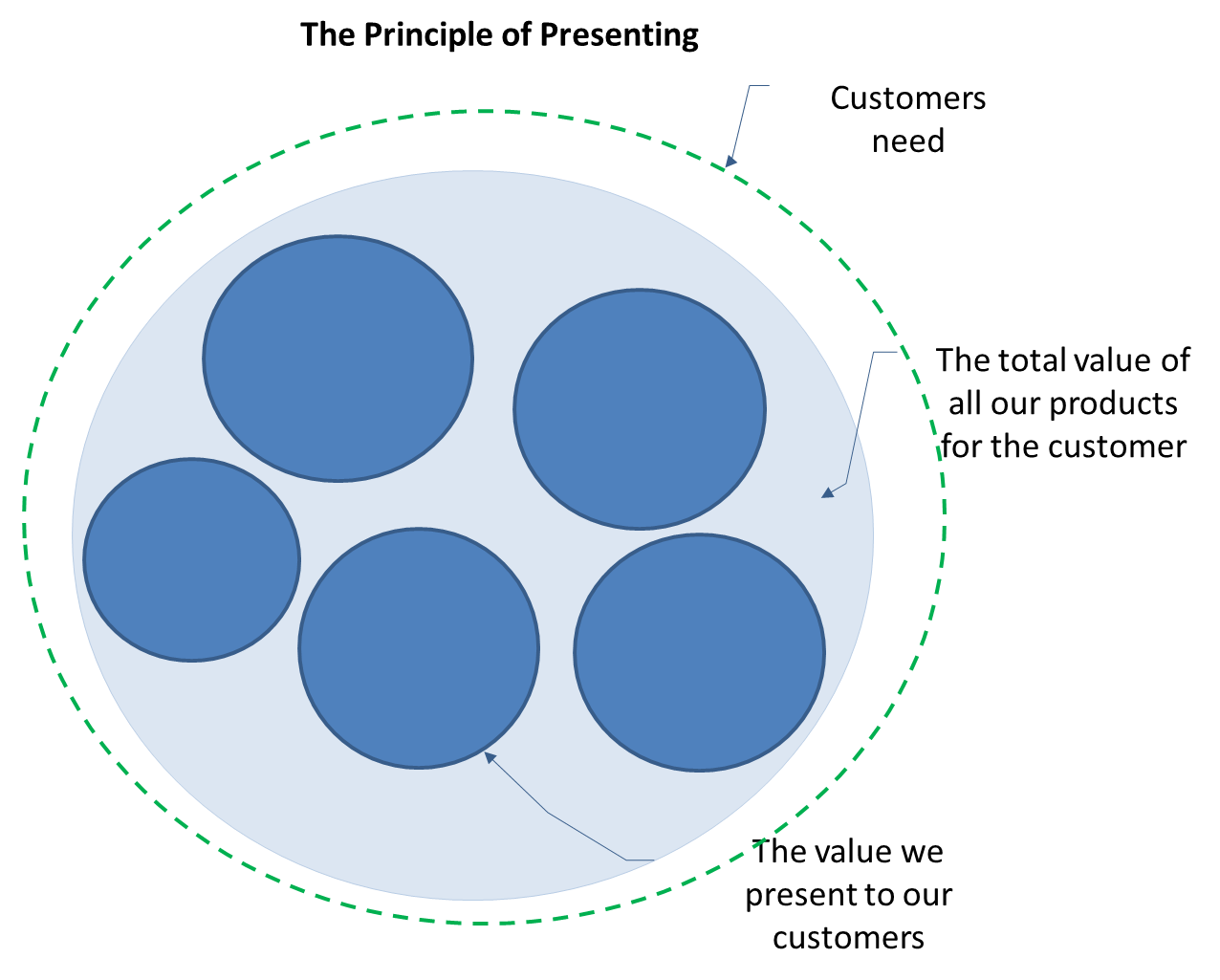

The Principle of Presenting stems from stitching together the product portfolio in a way that in its entirety logically meets the customer’s needs.

The concept behind the Principle of Presenting

The concept behind the Principle of Presenting is to tie all your products and services in a seamless interaction for your customers. In other words, minimize the gap between the combined value proposition of all your product’s offerings – your entire product portfolio – and the customer’s need. If your business looks and behaves with a single minded focus on meeting customer needs then you’ve got it mastered. But if it operates in silos, and makes the customer jump the hoops to understand and buy your products, then you have a problem.

There is only one question to ask:

- When a customer thinks about you, do they think of the many different needs they have that can be met by the many products you have? Or can they automatically, instinctively, state their need in a way that ALL your products can collectively meet.

The difference is important. For example,

- Everyone may know that Citibank and Bank of American offer multiple products that can meet many different financial needs. But we can also probably guess the amount of budgets allocated to cross-sell and upsell.

- A local supermarket may offer loyalty, shipping, online ordering, mobile phone inventory look-ups, online recipes, email coupons, ingredient checks, allergy advice and many other convenience features to customer. Think of your supermarket. I bet that only a miniscule proportion of customers will know and use these features.

The costs of not adhering to the Law of Presenting can be seen by simply observing the multitude of advertising programs underway at most firms. When these programs are integrated with a seamless customer experience, then the gap between value and need is smallest. However when these programs are add-ons to the original value proposition offered, then you are simply not positioned to meet your customers’ needs. You are operating as multiple independent companies who offer these products. You are acting like a marketplace. And that opens up the doors for competition to jump in and chip away at your share.

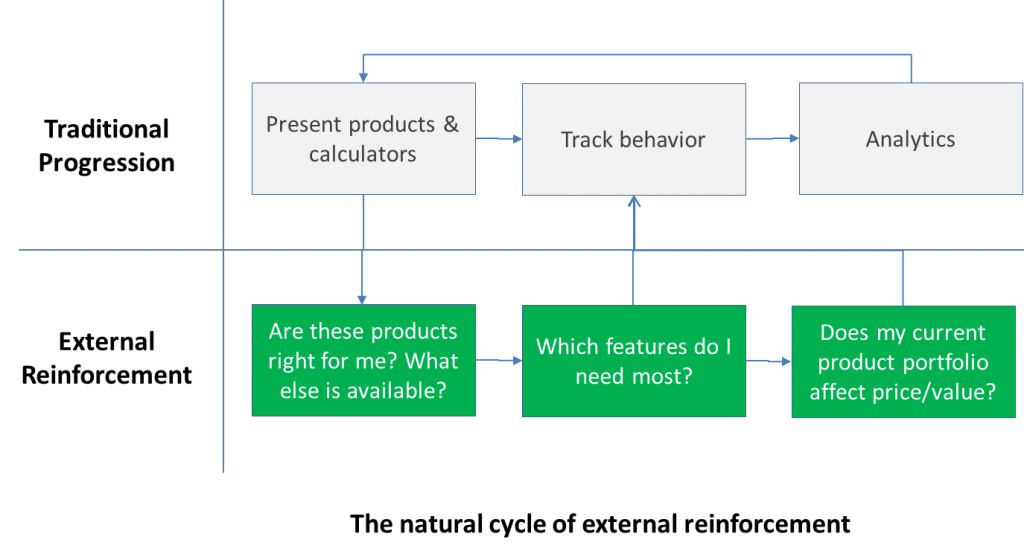

The Law of presenting starts by thinking about exactly that. Contrast that with how the products are positioned to customers today:

The gaps are obvious. There is a huge disconnect between what we are communicating and what the customers are capable of hearing. The digital economy has bridged the isolated communications channels. Customers have access to peer networks, independent sources of information and credible, voluntary advice from experts.

In a connected economy, customers don’t have to do more than fire up their internet browser and type in “reviews of <their product>” to get many different perspectives from many different people of all kinds. Not everything will be useful, accurate or objective, but it’s enough to make customers reconsider their initial choices and motivations. And just like in the case of the Law of External Reinforcement, if our products are not presented so they help each other with a singular focus on customer needs, our engagement with customers will be subpar.

But we seem to still approach them with individual products, failing to connect the dots with their overall needs. Our incentives are aligned by product, our organization is by product, our innovation is by product and it reflects in how we sell and market. In such a model we have to create and rely on cross functional programs to help bridge the gaps, and expect them to overcome the strongest barriers of all – people motivation. Why would someone support these programs when their incentives are aligned by their own product? As a result progress reports are published, metrics are adjusted to reflect positive sentiments and everyone goes home happy – without really making a dent.